GTA III's Definitive Edition is a reminder that great driving games are about chases, not races

They don’t tell you this going in but, for the vast majority of its running time, Bullitt is pretty boring. The classic car chase movie was shot during the rise of New Hollywood, when traditional notions of pacing and story payoff were going out of fashion, and largely follows Steve McQueen as he potters about an empty hospital looking for a sandwich.

But for ten blistering minutes in the middle, its wheels barely touch the ground. Maybe it’s down to the stimulatory deprivation of the scenes on either side, but the first time I watched McQueen take off in pursuit of two hitmen, riding their rear bumper all the way out of San Francisco, my arms were in the air—the same involuntary response induced by a rollercoaster.

The muscle cars, the free-rolling hubcaps, the chalkboard tyre screech, and especially McQueen’s wild wheel-twisting as he weaves through traffic—all of it informed the first generation of open world games three decades later. The scene effectively doubled as Driver’s design document, and Rockstar followed close behind: just as McQueen’s Mustang filled the rear-view mirror of his target’s Dodge Charger.

Bullitt established San Francisco—with its extreme verticality, tram tracks and dense junctions—as the international city of car chases. It’s a distinction that eventually led to its recreation in three Ubisoft open world driving games over just half a decade (Driver: San Francisco, Watch Dogs 2 and The Crew; full marks if you managed to name them all).

Today, though, the ground isn’t nearly so thick with car chase games. Driver is on ice. The Crew got distracted by a passing plane, and decided that was its new thing. Numbered GTA releases are now so far apart they’re recorded in epochs, not years. And Watch Dogs committed to capturing the streetplan of London, a city so notoriously bad for drivers that its locals were driven underground (please don’t check this with historians).

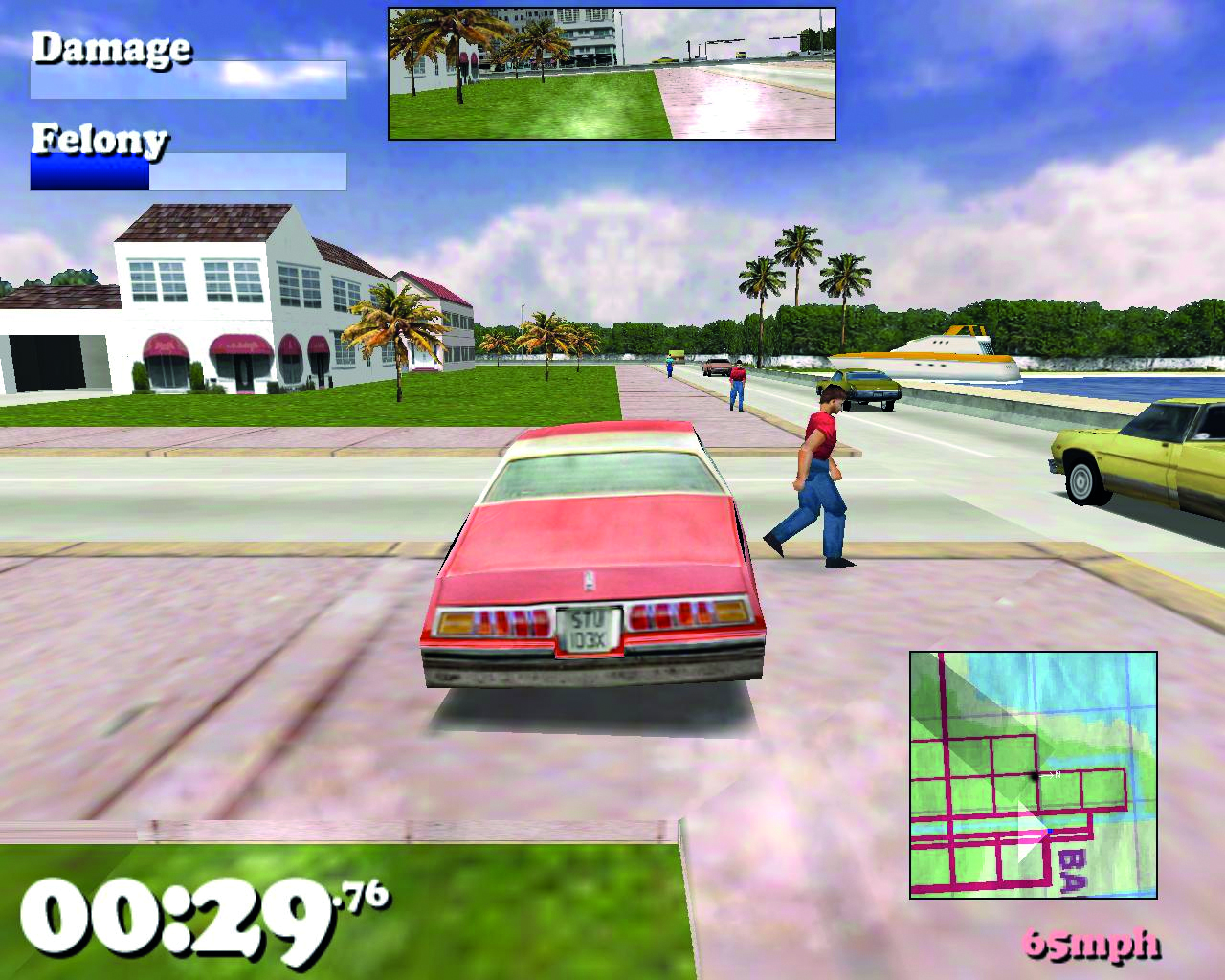

The upshot of all that genre stagnation and inactivity is that the classics haven’t been bettered. Those returning to GTA III with Rockstar’s Definitive Edition have found that, in stark contrast to its unrefined storytelling and shooting, the driving still stands up. Liberty City’s catalogue of sedans, flatbeds and ambulances remain twitchy and buoyant in a way that forces you to wrestle with them for control, making even the game’s many basic A to B missions engrossing.

There’s something perversely exciting about screaming through a city that hasn’t been expressly designed for that purpose. Since GTA III is built to be busy and interesting when traversed on foot, it’s frankly overwhelming at speed—stuffed with street furniture and civilian AI waiting to get tangled under your wheels. Crossing Staunton Island with your foot down is an act of extreme hazard perception, and survival a matter of learning to filter out the visual noise and focus on the obstacles that threaten to flip your ride.

It’s a very different experience to playing an arcade-y motorsports game, exemplified by the exquisite Forza Horizon 5. There, guard rails crumble and barriers bounce you back on course, like the training bumpers in ten-pin bowling. Everything on-screen is in service to the race and keeping momentum. By contrast, GTA III’s ludicrous, dangerous bustle generally feels like it’s working against you—as if, at any second, two men will walk out into the road carrying a sheet of plate glass between them.

In retrospect, GTA III’s best mission isn’t a scripted set piece at all, but the Vigilante challenge you can access from any police vehicle. It’s an endless generator of Bullitt-style car chases, in which you beat a timer to ram an escaping target off the road—preferably knocking them on their roof to trigger a favourite mechanical quirk of classic GTA, the upside-down-explosion.

With enough attempts you start to learn Liberty City’s three islands the way a taxi driver would, sniffing out the back routes and even grassy verges that save you from navigating the busiest thoroughfares. You’re able to look at the map and mentally add in the locations of all the police bribe icons that can get you out of trouble whenever a citizen’s arrest escalates. In fact, route-finding is a constituent part of these games—necessary to plot your way through a place that feels less like a circuit and more like an antagonist.

I sometimes wonder whether many AAA developers consider urban open worlds a relic of their past: a stepping stone in the journey that took them to Horizon Zero Dawn and Assassin's Creed Valhalla, rather than a subgenre to iterate and improve in its own right. But the city car chase is a fixture of pop culture; it was big in the ‘60s with Bullitt, and remains so today with the Fast & Furious films.

Hope lies with the next epoch of GTA, and with 2022’s Saints Row reboot, which put muscle cars and handbrake turns front-and-centre of its announcement trailer. For now, you can find me hanging around the car park of Portland island police station: Trying the doors of the cruisers, ready to deliver some road justice.

Post a Comment