Griftlands' complex double deck building shows promise in early access

It’s easy to feel cool in Griftlands. I can be a rough-and-tumble bounty hunter with an axe to grind, slinging cards and taking names. Or, a washed-up army-veteran-turned-spy who's looking for one last score and one more card to get me there. Wherever I am and whoever I am, the air is dusty and the bars are grimy and the drinks aren’t the only things on draft. Griftlands is, as you might have guessed, a card game.

Griftlands is the latest and slickest roguelike deckbuilding game, and it's of special interest because it comes from Klei Entertainment, the developer behind well-liked games Oxygen Not Included and Don't Starve. Like Klei’s other Early Access success stories, Griftlands is fun even before it's done, holding its own against the current cadre of killer deckbuilders, including Slay the Spire and Monster Train.

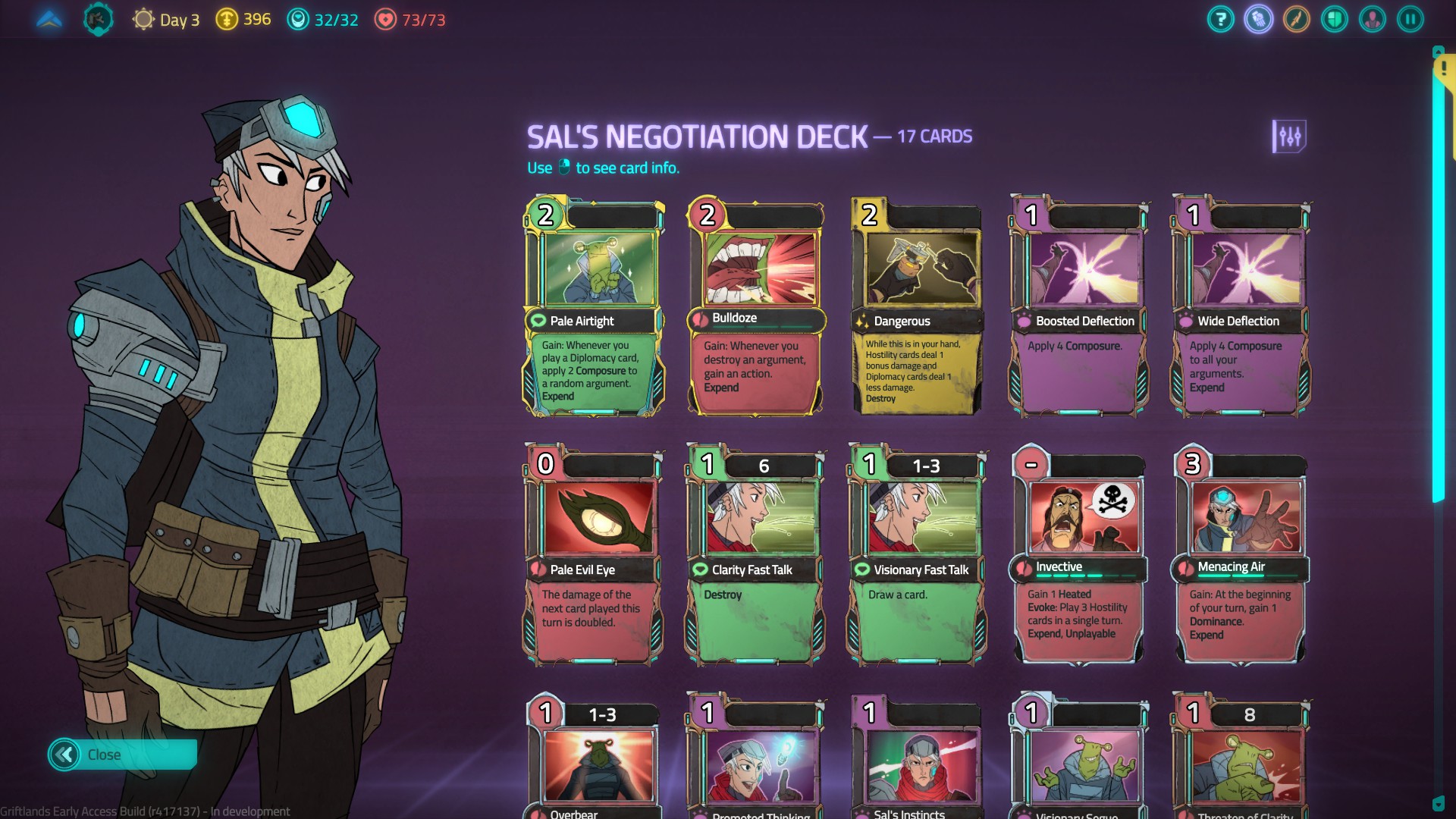

Griftlands' twist on the card game genre lies in its dual deckbuilding: You build one deck for fighting, and one deck for negotiating. Depending on the situation, you can pull out either deck to fight or talk your way to a resolution. The decks are kept entirely separate, but their underlying mechanics echo to each other. Both battle and negotiation decks have identical turn phases, basic attacks, and defence moves. You can build for similar concepts in both decks, like searching your library for cards or applying debuffs to your opponent. The similarities make it easy enough to pick up the basic elements of both battle and negotiation.

Negotiations begin to resemble a gameified debate class.

Even though the different decks are colour-coded, building two different decks with two different focuses for two different kinds of combat at the same time can get confusing. On more than one occasion I was left wondering whether a particular combo was in my talking deck or my brawling deck. On the one hand, building and working with these dual-decks keeps me on my toes, adding to the feeling that I’m a fly-by-night grifter, taking the wins where I can. On the other hand, building two decks at once can make for an overly-complicated experience.

I prefer the negotiations to combat, though they can be a little difficult to parse initially. Your attacks revolve around a “core argument,” your health becomes your “resolve,” and defense is rebranded as “composure.” You build up additional supporting arguments by playing cards, and use a mixture of cards and sustained arguments to attack your opponent’s arguments and resolve.

Negotiations begin to resemble a gameified debate class, and once your brain becomes accustomed to the swing of things, the mechanics shine. For example, opponents in the admiralty (space cops) can plant evidence on you. This creates both an easily exposed weakness in your arguments and a powerful sub-argument for your opponent called Interrogation. As play continues, your opponent’s Interrogation argument does damage to your Planted Evidence, which, if destroyed, does damage to your core resolve. If, however, you can defend the evidence through diplomacy, dominance, or manipulation, your opponent becomes Flustered, and their attacks become weaker. This is just one of many spinning arguments you might have to keep track of, and manipulate, in order to succeed in negotiation. Each one has a series of mechanical consequences, and leaves a richly complex game system in its wake.

A card game with a story

Everything in Griftlands is flavored by the game world. This is clearest in negotiations, where Diplomacy cards favour defense and composure, while Dominance cards favour aggressive attacks and intimidation. Manipulation allows you to search through your deck and play with card order, with the implication that you’re misdirecting your opponent in conversation. Cards with new keywords can show up as a consequence of your play style. After I murder an unsuspecting guard, for instance, I gain the card Reputation Preceding—it tells people I am not to be messed with by giving opponents an Apprehensive quality, which, in turn, gives me more defense when they attack. One of my favourite touches is that playing a card grants it XP on its way to an upgrade, so your most-used cards grow from use.

I’ve yet to build a deck as compelling as some of the infinite combos and damage machines I’ve created in Slay the Spire, but Griftlands has enough character outside of its deck building to stay interesting. The world of Griftlands’ NPCs is vast, and your character has a unique relationship with everyone. Most folks feel neutral towards you at first, but they can come to love or hate you depending on your actions. The resulting relationships create a complex web of consequences, serendipitous encounters, friends, and enemies—which can come to bizarre and interesting intersections.

Relationships play out by giving you social boons or social banes, which act as unique combat or negotiation modifiers. Sometimes, if you find yourself in an unexpected brawl or argument in a pub, friends and foes might intervene for or against you. In one instance, after I saved a religious fanatic’s life, I was able to leverage my friendship in order to get one of their parishioners off my back. In another instance, after I accidentally murdered a woman in the woods, someone publicly denounced me. Oops. I’d never heard of the man before, so I thought nothing of it. A few hours later it became clear that he was the head honcho of an operation I needed to infiltrate. Double oops.

Griftlands is at its most successful when I feel like a cool, fast-talking, combo-wielding rogue, and so it suffers where its dual deck building and keyword glut dazes and confuses me. Overall, though, there’s far more to love in Griftlands than not, and I’m excited to see how it grows through its Early Access cycle.

Post a Comment