Check out this never-before-seen StarCraft 2 concept art

StarCraft 2 celebrated its 10th anniversary this year, with Blizzard releasing a major patch that aimed to help map-makers create StarCraft 2 content for years to come. Meanwhile, Blizzard took PC Gamer on a trip deep into the past, revealing some never-before-seen concept art from the development of StarCraft 2.

When the idea of unreleased concept art came up, we naturally wondered: "Could StarCraft 2 have been a wildly different game?" Lead artist Rob McNaughton and game designer Matt Morris helped answer that, revealing some of the ideas that didn't make the final cut.

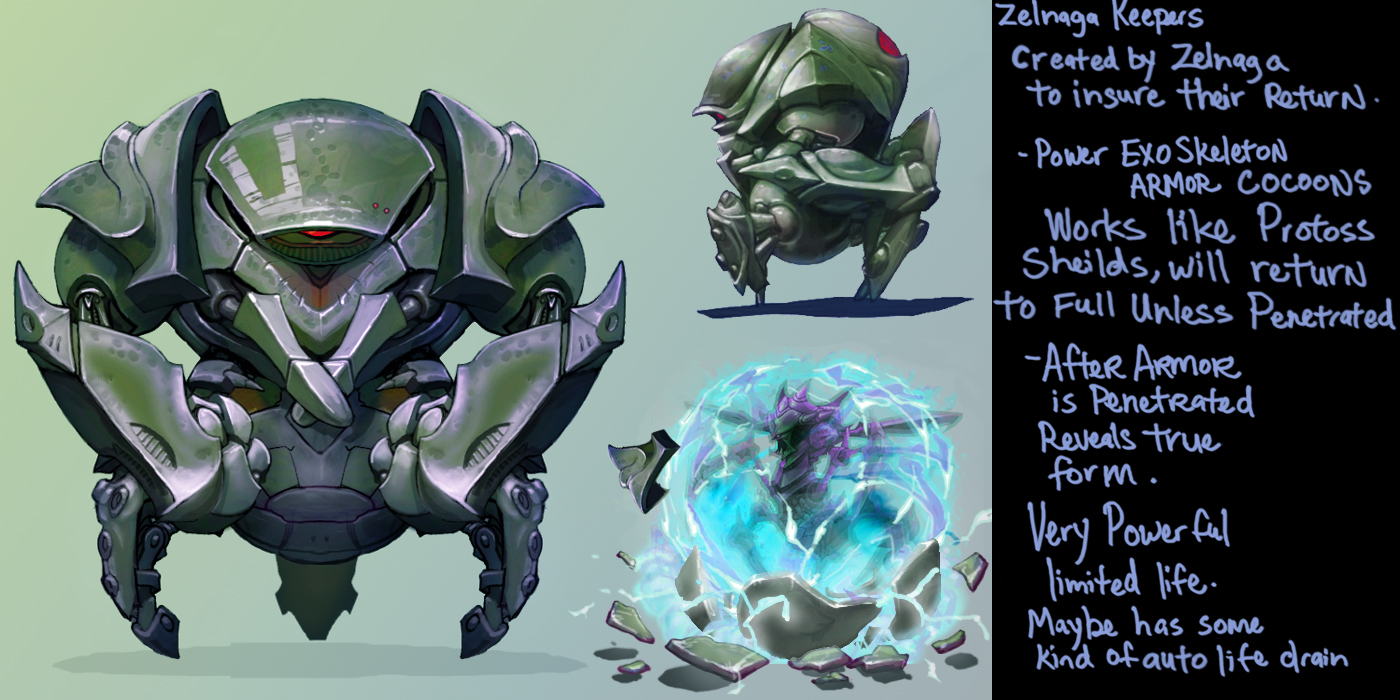

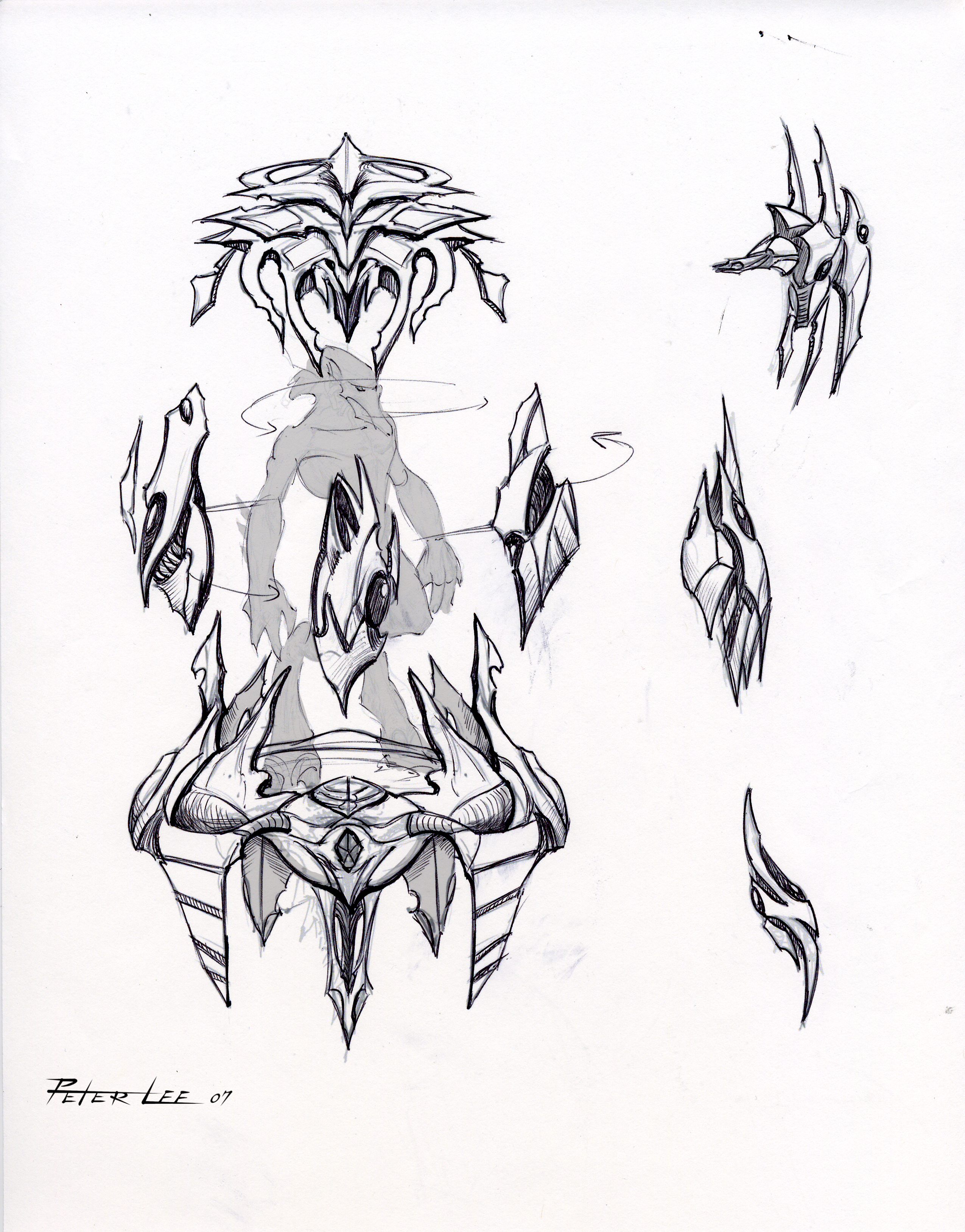

Inspecting the images from the vault, a file titled 'Xel'naga Keepers' stood out like a gleaming prize. The xel'naga were introduced as StarCraft's mysterious progenitor race back in 1998, and fans had been allowed precious few glimpses of this shadowy faction until the final SC2 expansion, Legacy of the Void. Was this a remnant of a prototype, playable xel'naga faction that had been scrapped early on in StarCraft 2's development?

The Xel'naga Keeper, alas, was not a true xel'naga unit per se, but an early imagining of what kinds of minions the all-powerful aliens might deploy to impose their will. "As we started working on the lore, we basically found that the xel'naga are too strong," explained McNaughton. Morris, who oversaw the singleplayer campaigns of StarCraft 2, said that "From a gameplay standpoint, the xel'naga were never really on the table for us to use." Drat.

The unit possessed a unique, two-stage mechanic, initially fighting with its robotic exoskeleton, and then unleashing a powerful psionic entity once the armor was broken. While the Xel'naga Keeper warranted "a decent amount" of discussion, it was ultimately determined to be too close in concept to protoss, and thus the cephalopod zerg-protoss hybrids ended up being the primary proxies for the xel'naga in StarCraft 2.

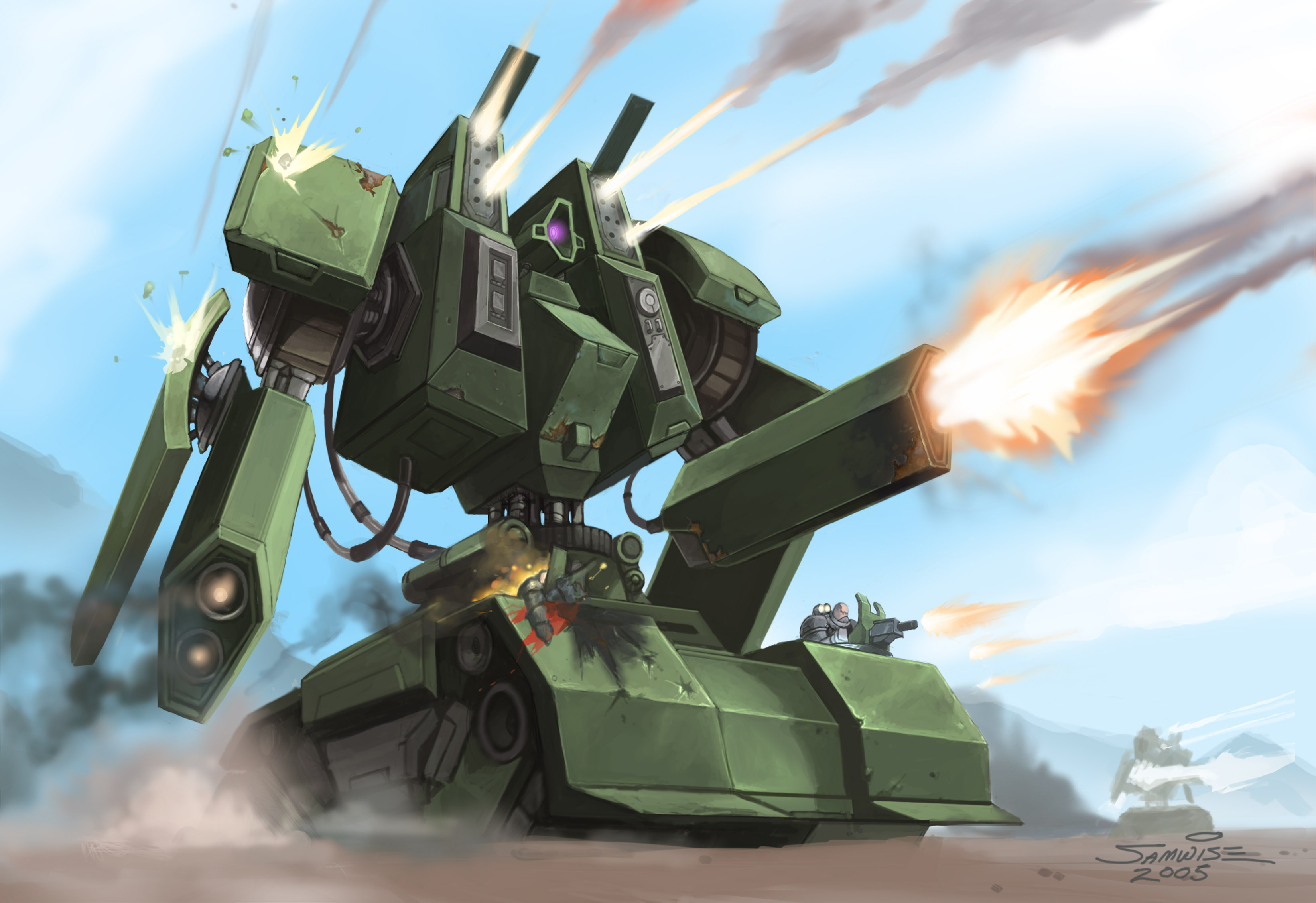

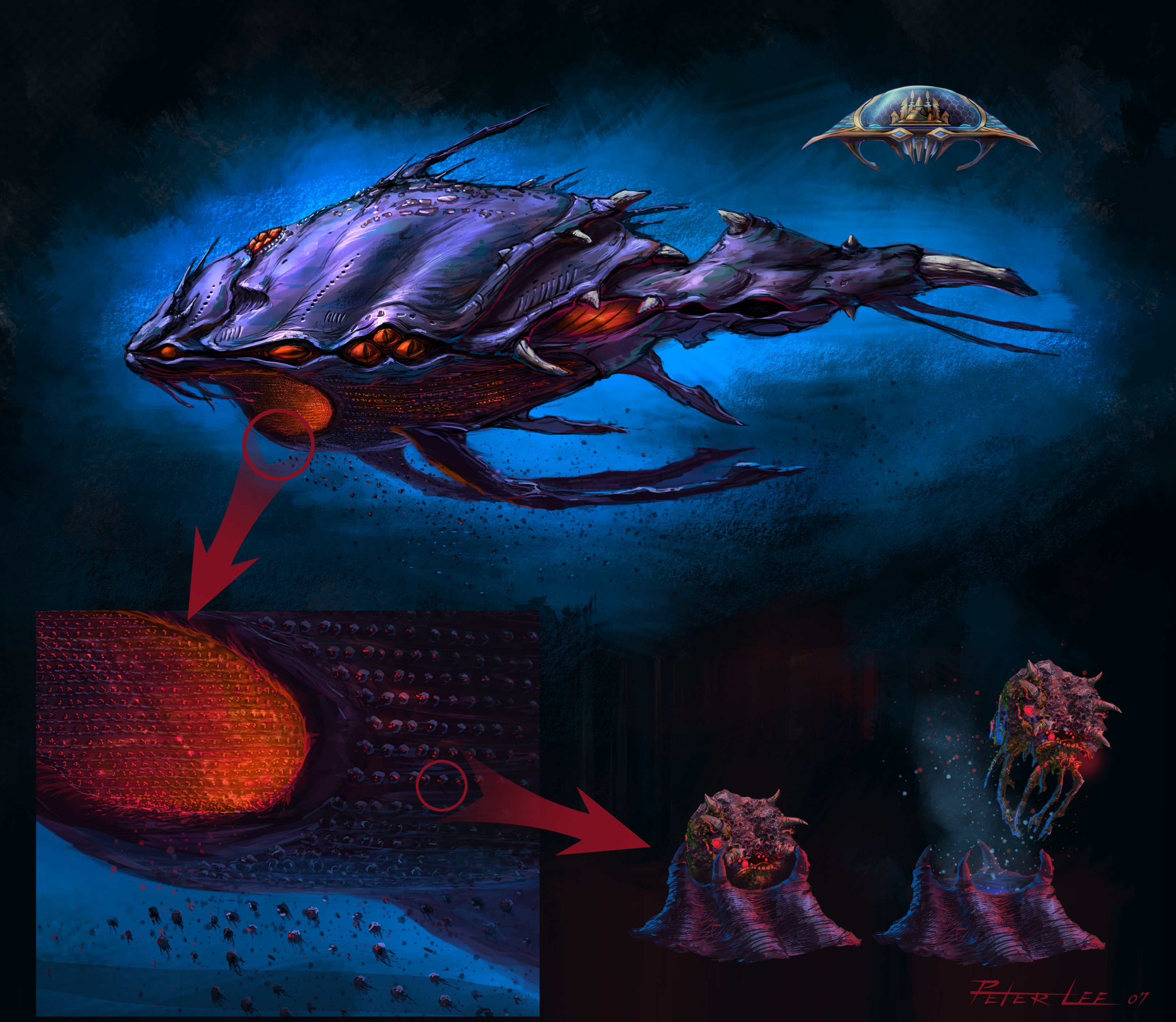

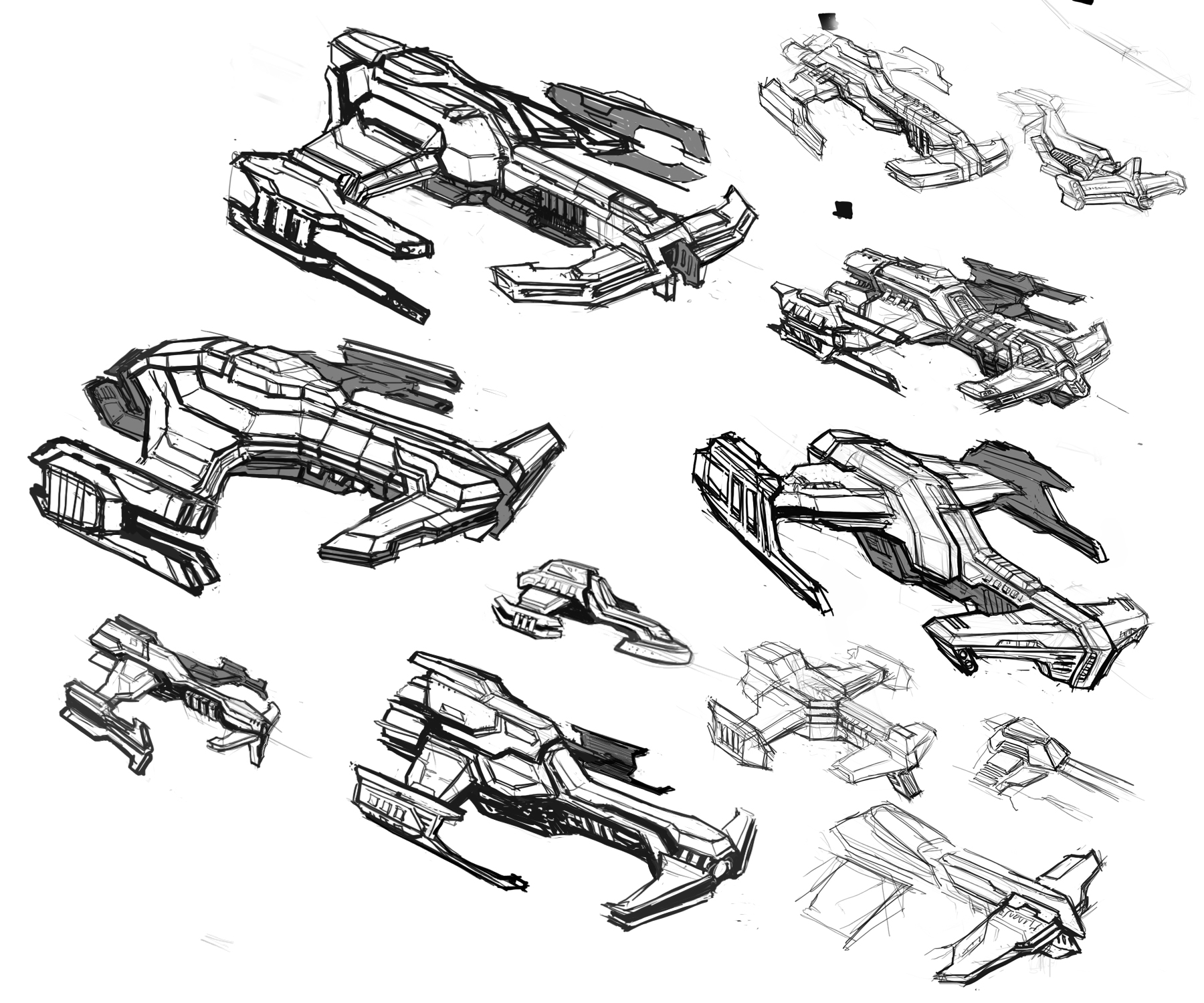

A more humorous discovery was made in the array of zerg concept art. While most of the creatures depicted were recognizable as rough sketches of units that would eventually be seen in StarCraft 2, there was also a peculiar artillery unit that seemed to turn around to bombard enemies through a posterior orifice.

When asked what about the unit, McNaughton could only answer with a question of his own: "Do you ever wonder where a Mutalisk shoots out of?" Well, I guess that's something that will always be on my mind whenever I see a Ravager use Corrosive Bile from now on.

McNaughton brought up another scrapped zerg unit as one of his personal favorites, one that would "stick its tail in the ground, and then shoot webs up at flying units ... the idea was that it could bring down an air unit so that Zerglings could jump on it", akin to the Crypt Fiends of Warcraft 3.

Ultimately, though, it didn't seem like much was scrapped wholesale or left to go to waste. The unit count was limited in competitive multiplayer for balance reasons, but the singleplayer campaign served as a refuge for cool ideas that needed a home. "A lot of stuff that didn't make it into the competitive mode actually made it into the singleplayer. Any time [an] artist would create a unit or model … we found ways to get it into our campaign," said Morris.

Morris did, however, have some lingering thoughts on a singleplayer mission mechanic that never saw light, where a dam would break and let loose a deluge of destruction. "We just never found a good fit for it," he said. McNaughton recalled another abandoned experiment, where a map would be divided into two layers. "The concept was way too hard, but it was an interesting idea—you'd have a space and ground battle going on at the same time." But even that idea was eventually actualized, albeit in another Blizzard game—the concept led to the Haunted Mines map in Heroes of the Storm.

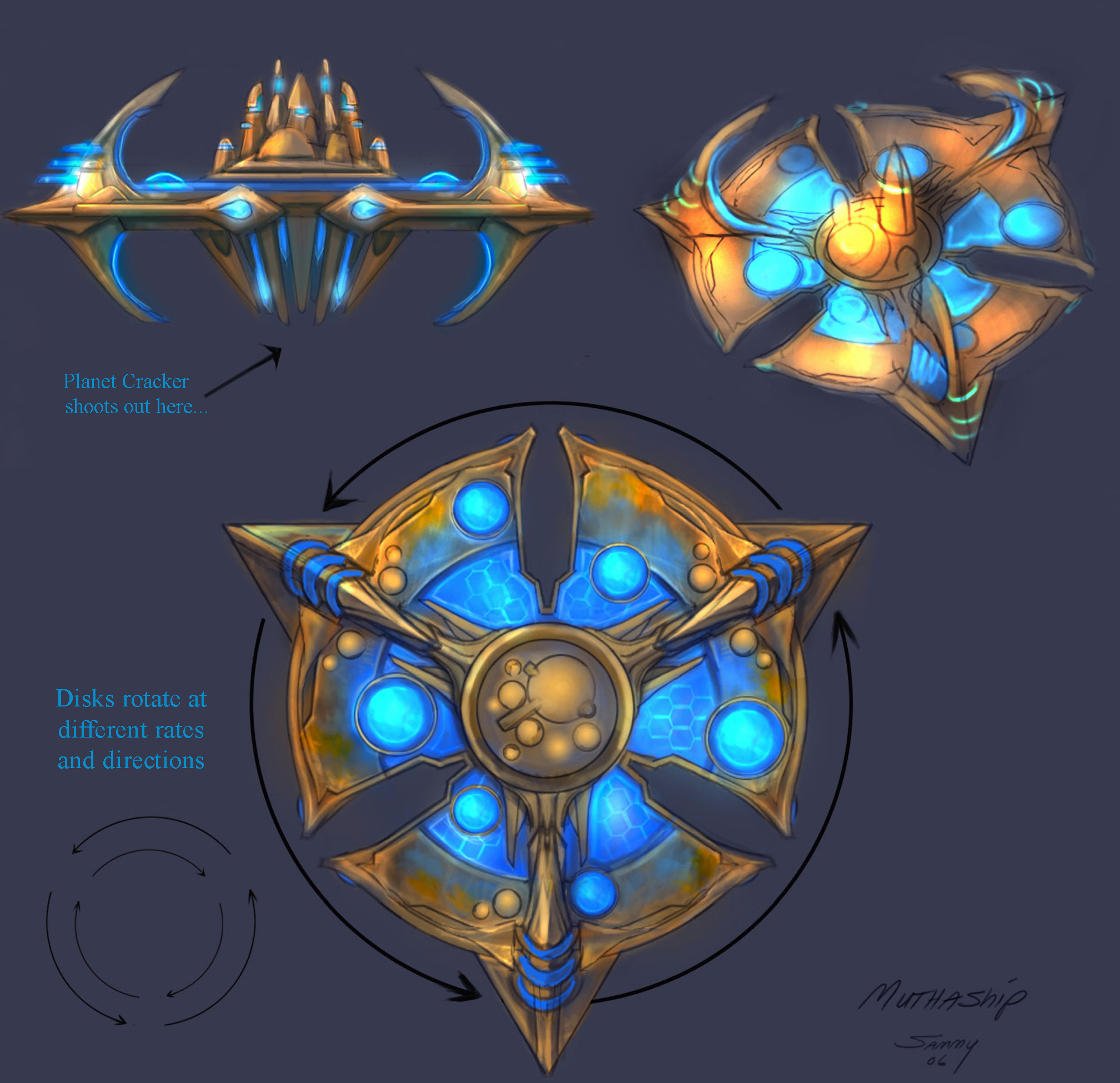

Beyond the individual units themselves, I asked if the development team had considered adjusting the general scale of the units for the sequel. One of the reasons the original StarCraft had captured fans' imaginations was the larger, galactic-level conflict it hinted at, even if it wasn't represented outside of loading screens and cinematics.

In making a sequel, the dilemma of 'how do eight Marines beat a single Carrier?' hadn't been lost on Blizzard. "During the making of SC2, we tried more realistic proportions, like Ultralisks being larger, Battlecruisers [and] Carriers being massive," said McNaughton. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a better idea in theory than in practice. "The next step is, though, to make Marines smaller, and the game becomes unplayable, instantly ... that really takes away from our competitive ability to play the game."

"It just comes down to gameplay first," said Morris.

That might come as a disappointment to the group of fans who were underwhelmed by how little StarCraft 2 diverged from its predecessor, compared to other Blizzard sequels like Diablo 2 or Warcraft 3. However, the developers reminded me why StarCraft 2's identity was so tied to staying true to the original StarCraft.

"We wanted this to be as close to [StarCraft] Brood War as we could," said Morris, elaborating on some of the "design pillars" of the game. "It was so popular with Korea … we didn't want it to go too far."

Indeed, the Korean server player-base for StarCraft 1 already outnumbered the rest of the world by eight to one in 2000, just two years after the game's release. Furthermore, the country had created a vibrant, StarCraft-centric esports scene well ahead of the Western esports boom of the 2010s. It wasn't surprising that many of the StarCraft 2 design choices were influenced by that existing fan-base.

"...From the philosophy of how we're designing the mechanics and whatnot, we wanted to stay as close to Brood War as possible because that was what people were familiar with, and we wanted people to transition from SC1 into SC2," said Morris.

In the end, I can't help but get the feeling that any radically different incarnation of StarCraft 2 existed more in the minds of the fans than in the heads of the developers. Was that for better or for worse?

Certainly, there's a bitter irony in the fact that the Korean audience largely eschewed this game made with them in mind, a game made with such deference to its predecessor. Yet, at the same time, this faithful adherence to StarCraft 1 ended up producing a game that sold millions of copies, kickstarted the revival of esports in North America and Europe, and helped Justin.tv become Twitch. 10 years later, StarCraft 2 has become a venerable ancestor in its own right—perhaps not yet to StarCraft 3, but to a significant part of modern gaming all the same.

Post a Comment