Almost 30 years after its release, I still can't get enough of the tabletop RPG HeroQuest

I don’t feel nostalgia for many things, but when I fire up HeroQuest and the music suddenly flips into Golden Brown (imagine being a composer, told you only have 30 kilobytes for your entire musical score and thinking, “Cool, that means I can fit this harpsichord solo by The Stranglers in”), I feel a full-blown Proustian rush.

The ad for the board game version of HeroQuest has the same effect. Like a whole generation of baby dorks I saw those kids saying “I’ll use my broadsword” and “Fire of Wrath!” and immediately asked my parents to buy it for me when Christmas rolled around. Then I played it with my parents, my friends and my babysitter until everyone was thoroughly bored. Even my babysitter didn’t want to play it anymore, and she was paid to spend time with me. I kept playing by myself, keeping the board set up on a tiny table for one under the stairs, controlling all the monsters as well as a full suite of four heroes. Now that I think about it this is actually quite a depressing memory.

What was great about the board game was that it came with such an excellent set of dungeon furniture and miniatures. That manic, grinning goblin is still the first thing I think of when goblins show up as level-one enemies in any game. The one-eyed fimir, right out of Warhammer, looked like a Ray Harryhausen monster. I still have a bunch of the plastic skeletons and mummies, which later became the core of an undead team in tabletop fantasy sports game Blood Bowl. The cards were lovely too, with their dopey, overconfident adventurers who’ve just cast Rock Skin or swigged a potion of strength.

Once you sat down to play it the game was really nothing special. Sometimes you’d roll to move and have one of those turns where you can’t get anywhere and just have to say, “I search for secret doors and traps,” and the Evil Wizard player would look at the map and say, “There are no secret doors or traps here.” (HeroQuest was one of those games where, as the kid who owned it and knew the rules, you’d have to be the bad guy and never get to actually play one of those rad heroes on the cover.) Some of the quests were a bit rubbish too, like the one where every door randomly teleported you to a different room. Honestly, to hell with that.

Gremlin Interactive’s 1991 videogame version keeps all of the worst things about HeroQuest and adds a few more. It has fewer equipment cards, so your wizard can’t buy a cloak of protection, and the AI is so daft it won’t even follow you to another screen. Those screens are tiny, only depicting one room or hallway – sometimes just a dinky three squares of dungeon. If one of the other heroes is standing on the edge of a transition between screens, finding the spot to click so you can move past them is a huge hassle. There are a lot of traffic jams.

The characters look ridiculous too, the barbarian a muscular toddler who waddles about like his diapers are full. The Amiga version was animated better but had fewer colours to work with, everything sprayed lurid purple like a psychedelic grape juice explosion. And that music I like so much? You can only have it or the sound effects on, not both at once. Every quest ends the same way, with a march across the map to get to the stairs and out. All the monsters are dead, all the rooms have been searched, but Johnny Barbarian Hero here wandered off to explore the far corner of the map and now has to spend several minutes rolling-and-moving his way to the exit. The wanker.

I had forgotten about this until now, but back when I was playing the board game with my friends I’d let them finish the quest and collect their rewards without having to walk all the way back to the exit because that’s boring. I took that spirit of ignoring the rules when they got in the way of the fun with me when I started running RPGs like Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play for that same group of friends. So thanks for that, HeroQuest.

When I was 12 years old the weaknesses of HeroQuest didn’t bother me much and honestly they’re minor annoyances now. I still manage to have a good time with it because all I want to do is roll dice and cast Fire of Wrath and use my broadsword. It’s admirably simple, letting you play any quest in any order, with an old-fashioned belief you can be relied on to find your own way through rather than having to be guided by unlocks, and there’s no levelling-up to worry about. You don’t have to kill every monster for the experience points because there aren’t any experience points, and can just walk past if you can’t be bothered fighting them. Jog on, Mr Chaos Warrior, I’ve got a Talisman of Lore to find.

The other thing to note about HeroQuest is that it’s clearly designed for hotseat multiplayer, up to four kids sharing a keyboard and mouse with the Evil Wizard automated. It existed to let children like me be the elf for once, and that’s all it had to do.

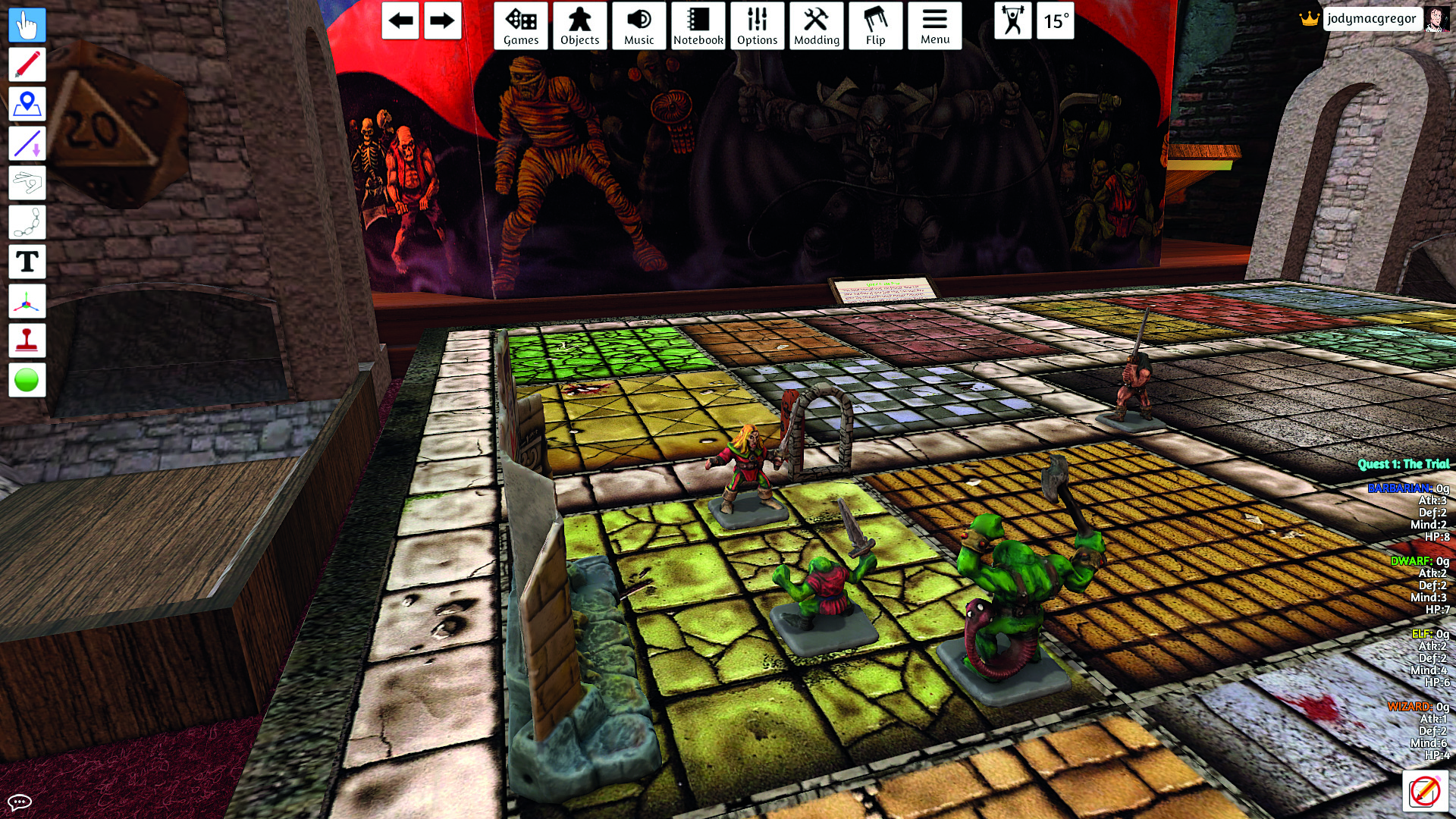

For a full modern digital HeroQuest experience you can play online there’s Tabletop Simulator, which has at least two implementations in the Steam Workshop, one a fancy version full of accurate 3D models for playing pieces and a fantasy tavern backdrop. The other one is a little more basic, though with animated monsters borrowed from another mod and a forest setting for an outdoor board game vibe. Neither’s what I actually want, of course. What I want is to be able to play by myself but with slightly more modern controls than a game that’s from 1991.

I turn to Lurchbrik’s Isometric HeroQuest next, an extremely competent fan game available for free, which should be perfect for me. But it’s based on the American version of the board game, which has slightly different rules, and 3D models that don’t look like the actual heroes and monsters. It’s just different enough to the game I grew up with that it doesn’t set off those pleasant memories, while the much more flawed official version from 1991 still does. What a ridiculous emotion nostalgia is.

Fortunately, there’s yet another option. The HeroQuest board game was followed by Advanced HeroQuest, and then a whole line of Warhammer Quest games. The videogame version of the first Warhammer Quest, made by Rodeo Games and released in 2015, is thoroughly decent. It gives me four heroes exploring dungeons in a turn-based fashion like I want, but with combat that’s a bit more tactical than a board game for nine-year-olds.

Warhammer time

Most fights in Warhammer Quest involve my ogre and warrior-priest blocking a doorway while the wizard and elf shoot over them. If you start a turn base-to-base with an enemy there’s a chance you’ll be pinned in place, so you can rarely rely on mobility to get you out of a jam and have to play defensively, though there’s always a chance an ambush will strike at your back line. I give the elf a magic sword and the wizard a stockpile of scrolls to burn through in case goblins launch a surprise attack at their backs.

Between dungeons everyone marches to the next town, each of which assembles itself out of digital papercraft in a nod to its cardboard roots, and also a bit like the Game of Thrones credits. Each rundown hovel presents a new quest in choose-your- own-adventure style. Here in Wurtbad the starving locals want me to bring back their only mule, Old Nell, who was dragged off by a giant spider. I rescue her, turning down an option to waste time grabbing fancy tapestries from the spider’s lair because Old Nell might get snacked on while I faff about.

The villagers are grateful, because it’s almost festival time and they were out of animals for the feast. I rescued their favourite mule just so they could eat her. But then I’m offered two of Old Nell’s haunches as a reward, which turn out to be solid healing items. So I guess we’re going to eat her now as well.

These grimy low-rent stories do remind me of something I liked about HeroQuest. It promised “high adventure in a world of magic” but then you’d get treasure cards explaining you found a few coins in a smelly old jerkin, or a single small gem hidden in the toe of a boot. Sometimes you’d find nothing at all, complete with an illustration of a broken-down goober of an adventurer holding out empty hands. The Castle of Mystery, the quest with the teleporting doors, rewarded you with a chest full of gold only to reveal at the end it was fool’s gold, completely worthless. In fact so was every bit of gold you found in that dungeon—even the coins in the smelly old jerkin. Pah!

Low-rent heroes scrambling for crap rewards in dirty dungeons, not even earning enough to buy that crossbow they’ve got their eye on. That’s what these games are really about. There are rats on the furniture and the monsters are all slightly more menacing than they need to be for ages nine and up. That’s what lingers about the experience of playing HeroQuest in either form—the idea that there’s less glamour in heroism than you’ve been led to expect, and that sometimes you have suck it up and be the player who searches for secret doors and traps.

Post a Comment