Everything is a visual novel now and it rules

There are plenty of games with an huge amounts of words in them, and sometimes people call these games visual novels in a smartarse way. Disco Elysium, for instance, contains thousands of words of novelistic prose. It's not a visual novel, though. At no point does the action pause so that a portrait of your partner Kim Kitsuragi can slide in from screen right, play a sound effect like a cartoon slap, and then slowly fill a text box with ellipses to suggest how horrified he is to catch you stealing a dead man's shoe while wearing a culturally insensitive hat.

That sounds like a pretty fun game, but it's not what Disco Elysium is. Disco Elysium is an RPG that just happens to have a lot of writing in it.

That said, there are games on the spectrum between the classic visual novel where you cry about characters in high school and the classic non-visual novel videogame where you get to stab a stand-in for your dad at the end. And there are more of them than ever before.

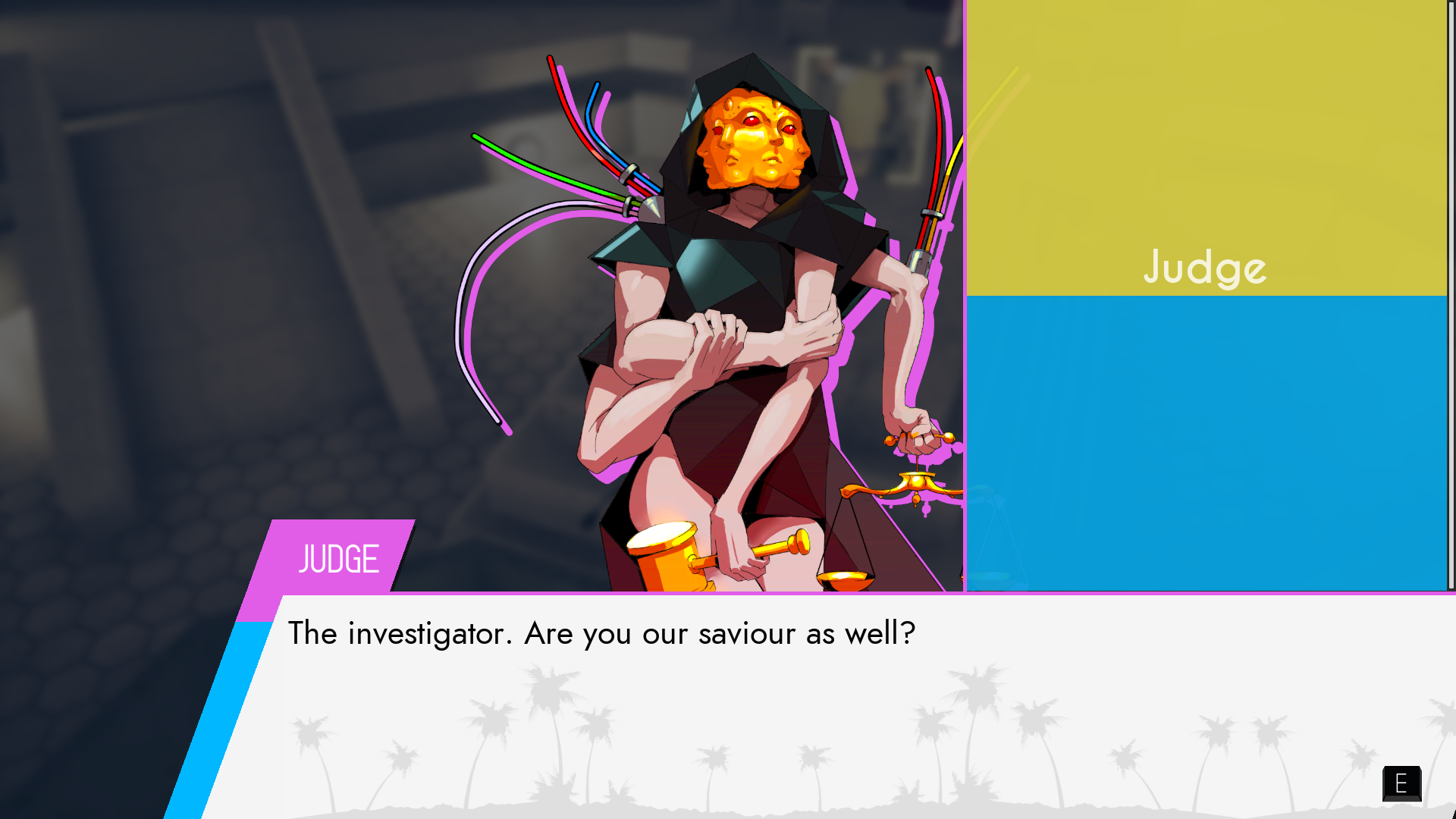

I have a lot of respect for the way Paradise Killer tricked people into playing a visual novel. That's a glib way of saying what I mean, which is this: Paradise Killer blurs the line between visual novels and adventure games, much like the Ace Attorney and Danganronpa games that inspired it, by making you explore a space looking for clues. But Paradise Killer goes even further into the territory we normally associate with "real games" by giving that space the kind of level design you'd get in Unreal Tournament multiplayer maps.

Paradise Island feels like a bunch of custom deathmatch maps stuck together. There's a beach covered in obelisks, a waterway with ladders that invite you to climb down and then back up it, Grecian pillars that grow out of fountains, and statues—so many statues—of skulls and gods and ladies. It even has a ziggurat. It was made in the Unreal Engine, and it feels like it.

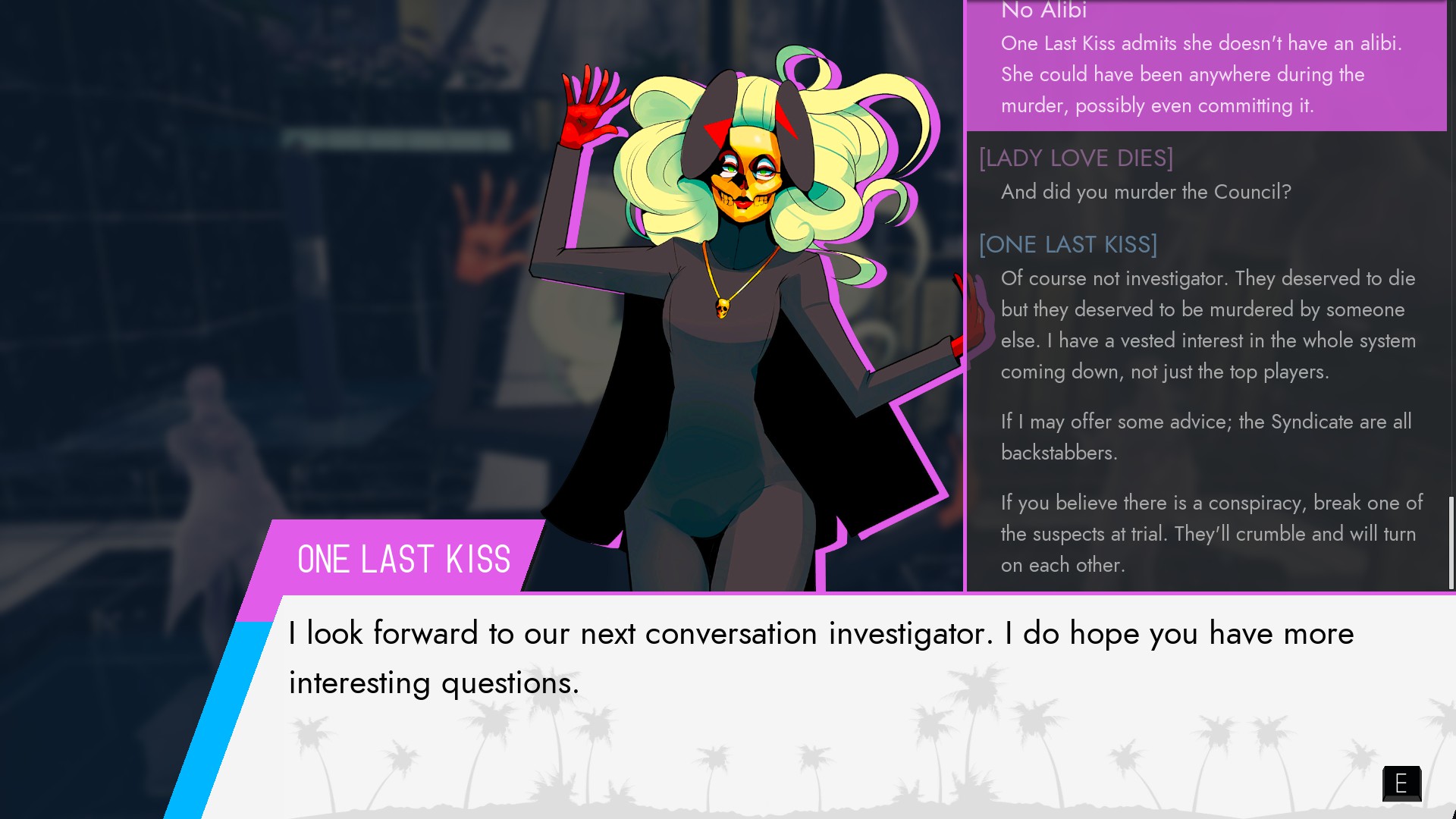

But this isn't a place you go to camp the flak cannon. It's a place where you solve a crime by talking to characters represented by 2D portraits that move between a handful of expressions (including one of shock that you're going to see a lot) and bark a handful of spoken phrases. Otherwise they speak through dialogue boxes, preserved in a log so you can scroll back for anything you missed. At the end of the game there's a trial where you present your evidence and make your case, but in the meantime you grill odd-looking characters about their alibis and motives, and then are given the option to "hang out" with them.

That's the most visual novel thing about Paradise Killer. It suggests the kind of game where you select which characters to spend time with each day, then realize too late you've committed fully to one of them and been locked out of the rest—or that you weren't supposed to spread your time so thin and now, by not committing wholeheartedly to a specific NPC the first time you meet them, are stuck with a bad ending where you're forever alone. But Paradise Killer is not that kind of game.

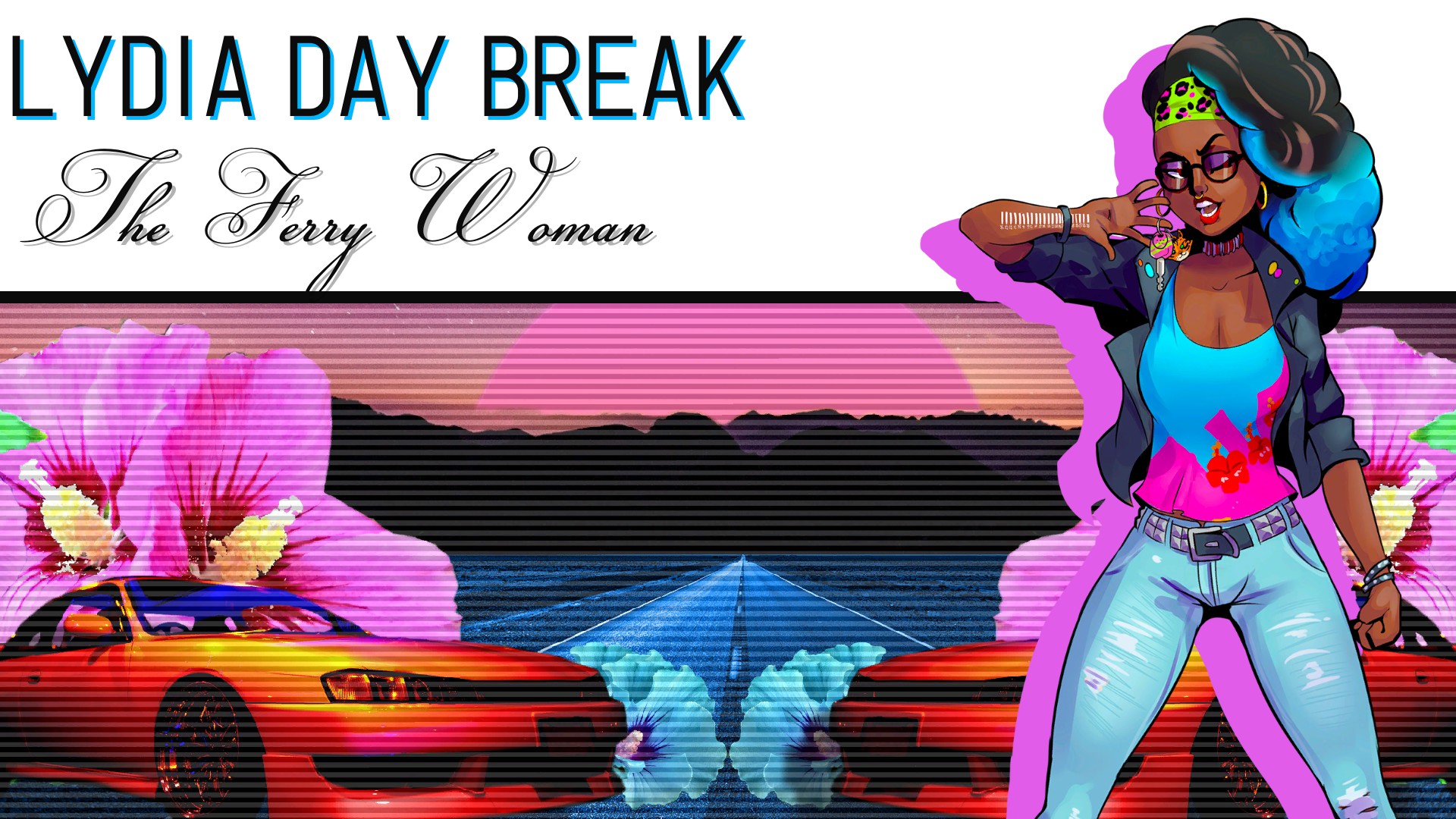

You're supposed to hang out with every character as often as possible, even the guy possessed by a demon who has been accused of murder, because getting to know them is how you get them to let their guard down and give up some vital piece of evidence. Paradise Killer may borrow the language of visual novels of the dating sim variety as well as the Phoenix Wright variety, but it's not going to punish you for deciding you'd really like to hang out with both the doctor on his yacht and your driver who poses with her car like she's shooting an album cover.

Paradise Killer wants you to see it as a gamey game, which is the technical term for videogames that provide you with a variety of verbs beyond 'talk to' and 'examine'. This is how they get you. You're hacking computers and finding secret areas, gathering collectibles and unlocking mobility upgrades—Paradise Killer has a double-jump, which is the most gamey game thing ever—and you don't realize that between all that stuff, you've been reading for hours while 2D characters gasp.

They got you, kiddo. They made you play a visual novel, and they made you enjoy it.

In Japan, there's been overlap between visual novels and games in other genres as long as they've been around. Adventure games like The Portopia Serial Murder Case, dating sims like Tokimeki Memorial, and life sims like Princess Maker all contributed to the big picture of what visual novels look and play like.

Broad as the term is, there's value to considering them all under the one umbrella. If someone says they like Monkey Island and you say, "Oh, you like adventure games? You should play Ace Attorney," then you have steered them wrong and they probably won't thank you. If someone says they like Christine Love's 2012 visual novel Analogue: A Hate Story but they haven't played Ace Attorney, that's a much better recommendation.

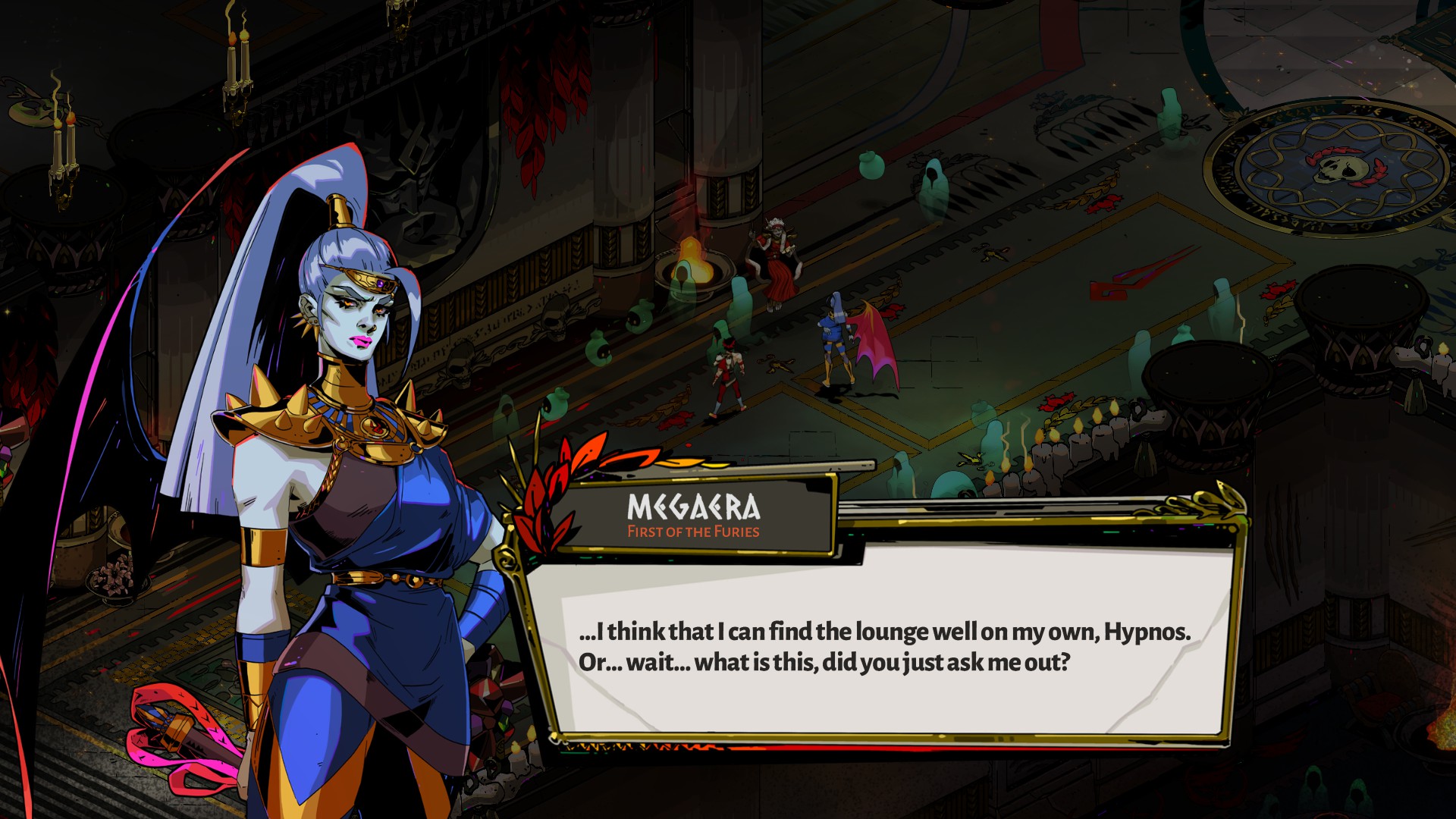

Hades is obviously not a visual novel. It's a run-based game, a roguelike, though one that appeals to people who don't normally like that kind of game. If you google "roguelike for people who don't like roguelikes" you'll be halfway down the second page before you find a result that isn't about Hades.

That's because, unlike Rogue or Spelunky or Dead Cells, it doesn't punish you for dying. It rewards you with character scenes that borrow their trappings from visual novels. When you return from another failed attempt to move out of your dad's house, you get to talk to the maid with a secret crush, your former best friend who is mad at you, or your ex-girlfriend who left some stuff in your room, which she'll definitely be around to collect at some point. The first is a snake-haired gorgon, the second the god of death, and the third is First of the Furies, born of blood spilled by the sky father's castration at the hand of his son—but they're interpreted through an extremely anime lens. You can even try to date them.

Companionship in Hades is a matter of choosing who to give nectar to. You have a drink with someone and immediately become closer. It's like dating in Australia. There's a backstory about how nectar is banned in the underworld and sharing it has become a trust exercise, an illicit bond, but the game effect is you hand someone a jar of friendship juice and one of the hearts above their portrait in your encyclopedia gets filled in. Some characters have locked hearts that won't fill until you do a favor for them, a little sidequest, which is how the romanceable characters become romanceable.

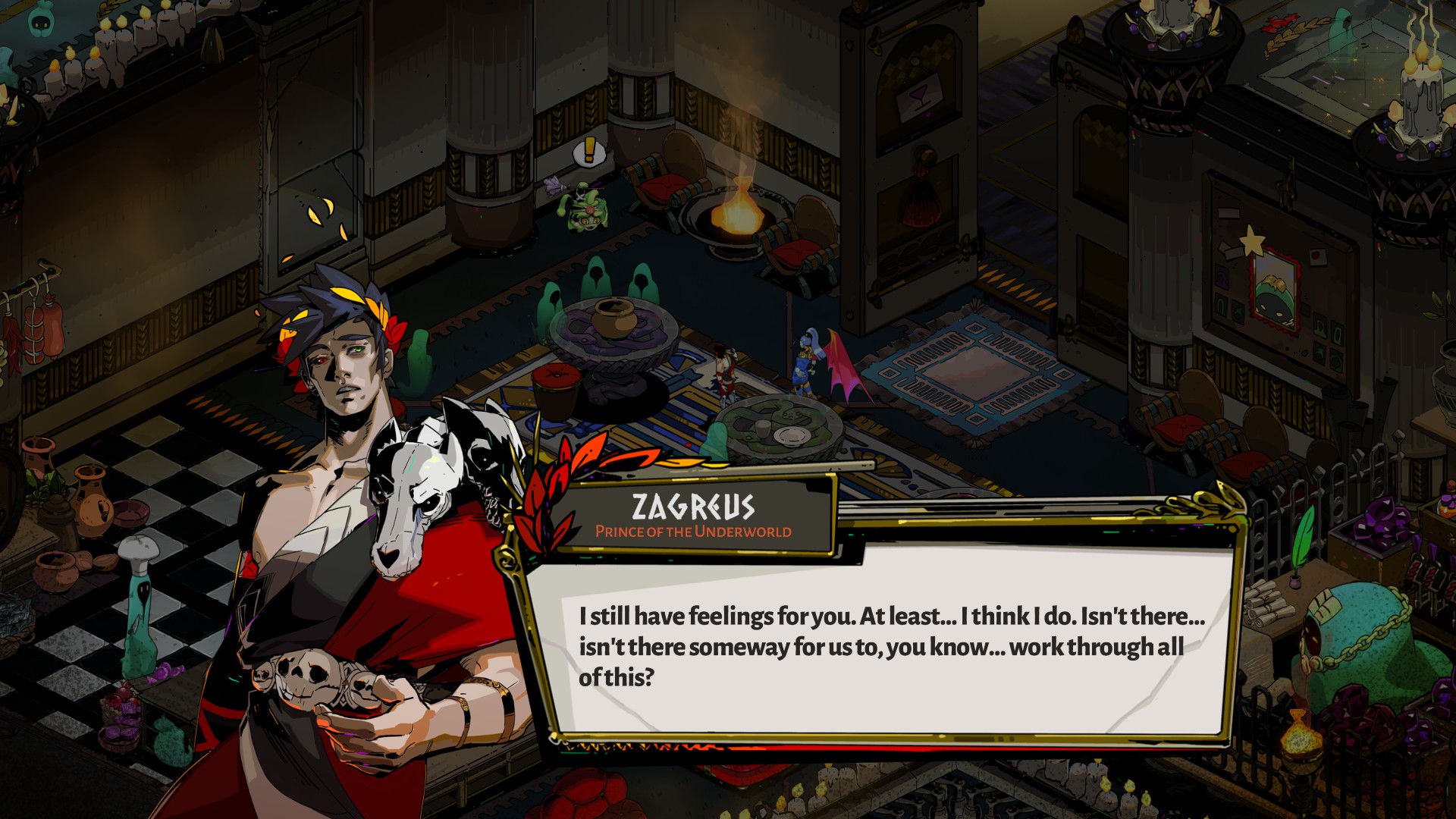

Hades didn't have to present its conversations in this visual novel-esque form. Every line of dialogue is voiced—it could just as easily have depicted characters as rudimentary talking heads or had simple comic-book cutscenes, but instead they slide in front of the action in the familiar way. When Zagreus confesses he still has feelings for Megaera he uses three sets of ellipses. Three. I rest my case.

The cross-pollination of influence between games where sprites are reused in front of background art and games where you slowly accrue more hit points continued in Japanese games as well, especially in RPGs like the Fire Emblem and Persona series. In the west it's less obvious but still there, like in Haven, an RPG by French studio the Game Bakers.

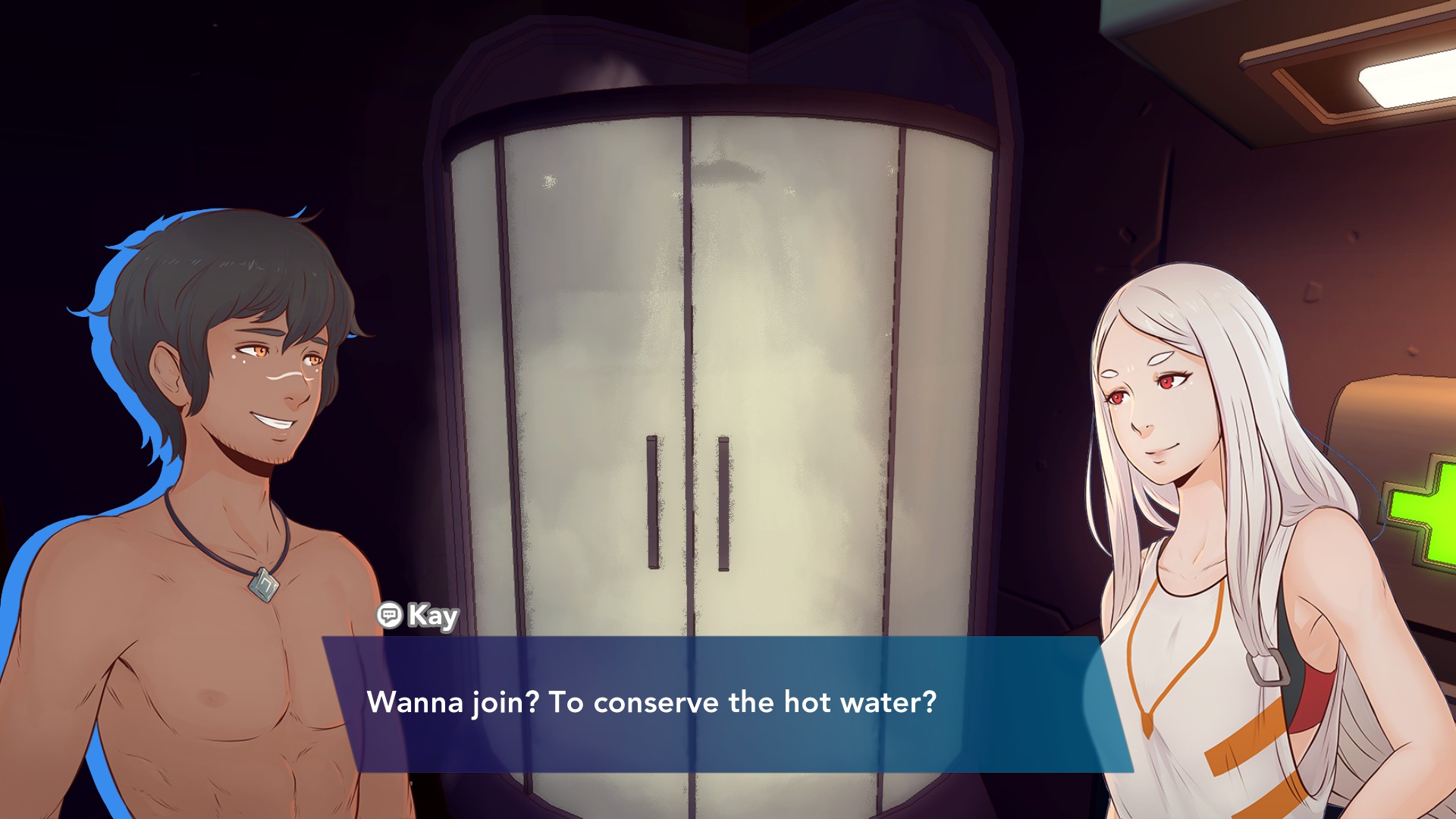

Haven is about young lovers who escape an oppressive sci-fi regime to hide on an alien planet together. They glide across its floating islands using anti-gravity boots, defeat hostile wildlife using a JRPG-ish menu timer battle system, and collect crafting ingredients. Then they go back to their crashed ship and enjoy some cosy domesticity, at which point it 100 percent becomes a visual novel.

Yu and Kay, Haven's protagonists, are in a relationship at the start of the game. They've already maxed out each other's hearts. Although dialogue choices can increase each one's confidence, they were in love and committed before you even pressed play.

The combat's nothing special and the gliding controls are fiddly, but the comfortable back-and-forth of Yu and Kay's conversations is precious. They squabble, but not so much that you wonder why they're even together, and they always make up. I didn't realize how much I wanted something like this until I was playing it—a mature depiction of a relationship that's well past the courting stage.

There are experience points in Haven, but you earn more of them by having a nice meal and going to bed than by defeating aliens. The points represent the relationship deepening, and to level up you go to the still, at which point Yu and Kay celebrate by getting tipsy on space moonshine.

Where so many game romances, whether in visual novels or otherwise, are about winning someone over (or choosing from a selection of potential lovers as if they're up for auction), Haven uses the dating sim format to depict an existing relationship. You're not choosing how to spend your precious bars of free time to make sure you get the girl while also keeping your grades up. All the activities represent domestic pottering—eating meals together or arguing over who should clean the shower, playing board games and doing the gardening.

It even remains wholesome when they try psychedelic alien mushrooms together, like two thirtysomethings having ecstasy for the first time at a dinner party.

Plenty of players don't consider visual novels to be "real games", whatever that means. But obviously game designers don't share those prejudices, and we're seeing the aesthetics and structures of visual novels bleed over into other genres more and more often.

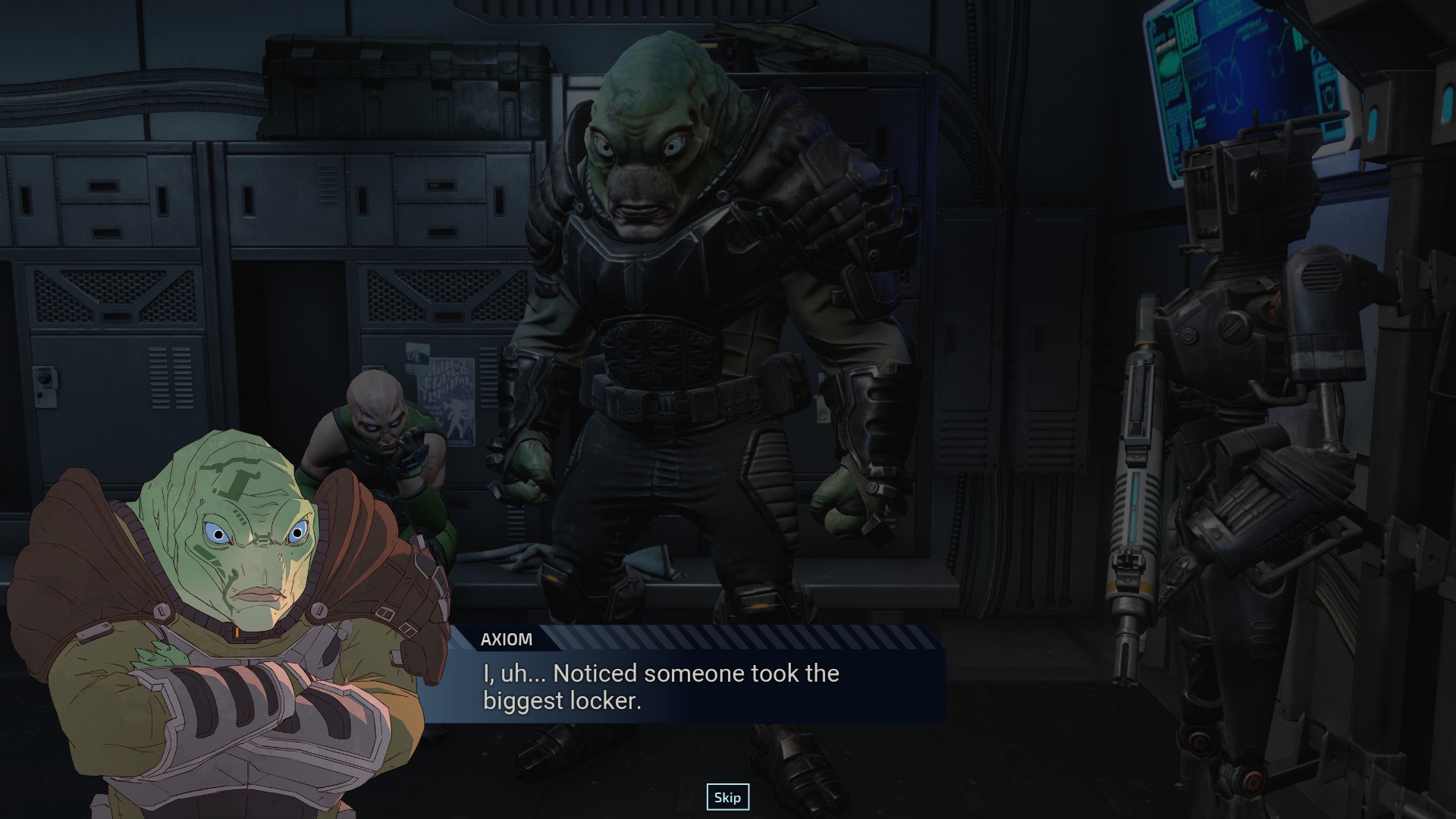

Even XCOM: Chimera Squad—a tactics game with variable weapon damage, percentage chances to hit, and three upgrade currencies—looks like a visual novel. It's the first game in the series to give your squadmates preset personalities, and in deciding how to do that the developers at Firaxis ended up with something like the Sunrider games, which cast you as the captain of a spaceship given command of a giant robots who fight on a grid—only instead of a cast of schoolgirl mecha pilots, Chimera Squad is about Saturday morning G. I. Joe action figures who trade locker-room wisecracks. This, I should add, totally rules.

When games want to portray character development on a budget, whether in a strategy game, an RPG, an adventure game, or whatever, the toolsets visual novels have been using for years are perfect for the task. The boundaries between videogame genres have always been blurry, and it seems like half the indie games on Steam mention having "RPG elements" no matter what kind of game they actually are. The wall between visual novels and gamey games feels like it's taken longer to break down outside Japan, but now that it has, we're one step closer to the Warhammer 40,000 dating sim you know you've always wanted.

OK, the Warhammer 40,000 dating sim that I've always wanted.

Post a Comment