How Disco Elysium Went from a D&D Group to a Huge Hit | Game Rant

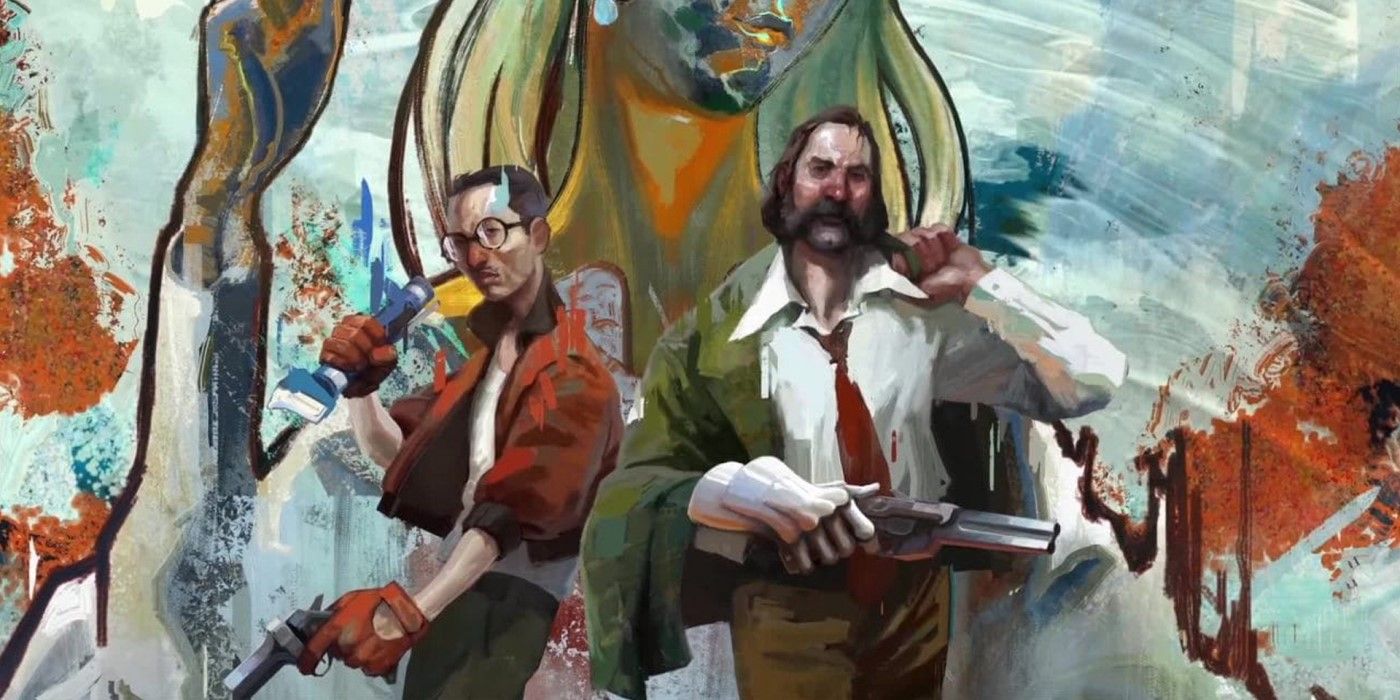

Amid the tar-stained rooftops and bullet-pocked concrete of harbor-front Martinaise, a man wakes slowly from a drunken stupor. He is naked, alone, and sprawled on a stained motel carpet. He is also the protagonist of one of the best games and RPGs of 2019 out there. This is how Disco Elysium begins. The protagonist, having experienced only a brief interaction where his own primordial hind-brain begged him to remain swaddled in the blissful oblivion of unconsciousness, is cast adrift in a strange and unfamiliar world. Now Disco Elysium's player must guide him to piece together not only a brutal murder, but also the shredded remnants of his own personality.

Disco Elysium was perhaps the biggest surprise of 2019, a game developed and self-published by a tiny Eastern European studio, that somehow found itself topping several Game of the Year awards. Among many critics it beat out triple-A titles such as Control, Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice and Death Stranding to take the top spot, but how did it do it?

If it was possible to define what makes a surprise hit, then there wouldn't be any. Instead, we can only look back on a game's development, and isolate those elements that factored into its success. For Disco Elysium, these elements include its excellent writing, its satirical commentary, and its beautifully-realized world-building. In many ways, it is a grim game, a game about defeat. The protagonist was defeated, which lead him to that booze-stained motel carpet, but also his city was defeated, setting the theme around which the entire story plays out.

The game takes place in the Martinaise district of Revachol, a sprawling city at the heart of Disco Elysium's steel-punk, eastern-bloc-inspired world. Fifty years ago, Revachol was torn by a bloody socialist uprising, and then crushed beneath the coalition of nations that invaded to restore order. Their sea-borne attack began with a heavy bombardment, and Martinaise was where the shells fell hardest. Even fifty years on, the district has not recovered. Crumbling bullet holes stitch random patterns across the harbor walls, and old craters pock the winding streets.

Just as the remnants of the war remain, so do the remnants of the socialist revolution that prompted it. With practically zero official police presence, Martinaise is controlled by a union of dock-workers; An organisation whose corruption is perhaps a necessary defense against the free-market forces trying to stamp them out. Strikers and scabs hurl insults on the picket-line, and in a forgotten backyard, a rotting corpse swings on the end of a make-shift noose. Enter our initially-nameless protagonist, tasked with investigating the hanging body, but hampered by the fact that he's gone so far off the rails he can't even see a station.

Disco Elysium's unique style of both art and game-play make it difficult to form comparisons with other games. Perhaps the most apt is the classic isometric-RPG Planescape Torment, with which it shares a perspective, a focus on dialogue and narrative, and a world built through evocative hints and flavorful dialogue. Disco Elysium is certainly an RPG, but not in the Dragon Age, Pillars of Eternity, or Witcher sense. Instead of a cast of colorful companions, the protagonist has the various aspects of his personality that players can invest skill-points into. Just as with Garrus, Eder or Vesemir, the protagonist may finding himself debating a situation with his sense of Drama, his Composure, or his Empathy.

Each Skill is given a unique and consistent voice, which helps keep them separate as characters. The drug-fuelled Electrochemistry is pure Id, hopped-up and demanding to know where the next hit is coming from, while the loquacious Drama is as theatrical as you'd imagine, often referring to the protagonist as Sire in their interactions. There is only one companion who doesn't ride along in the protagonist's head, and that's Kim Kitsuragi, the protagonist's straight-laced and endlessly patient partner.

If these aspects were removed, what was left would actually be quite easy to compare to a classic point-and-click adventure in the style of Monkey Island or Broken Sword. Just as in those games, the plot is driven by exploration, dialogue and problem-solving. Clicking on colored orbs in Disco Elysium often causes the narrator in the protagonist's head to comment on the world, somewhere where the game's excellent writing shines through. But to find the origins of Disco Elysium's beautifully-realized world and slick prose, we have to go back to the game's humble beginnings.

RELATED: Top 10 RPGs of 2019

The Disco Elysium story begins back in 2005, with a group of young creatives in the Estonian city of Tallinn playing D&D. The home-brew world their game is set in is an unusual one, defying genre but rich in atmosphere and politics. Four years later in 2009, members of the group found ZA/UM, an organisation of artists, writers, entrepreneurs, and activists who share an interest in politics and philosophy.

Initially there was no thought of ZA/UM making a video-game, and for several years the collective instead collaborated to produce music, paintings, books and expansions for their tabletop world. It was from this work came the genesis of Disco Elysium, or as it was initially known, No Truce With The Furies, and from three men in particular: Robert Kurvitz, co-founder of ZA/UM, Art Director Aleksander Rostov, and author Kaur Kender.

After having been advised by his children to stop writing books and start writing video games, Kender went to Kurvitz with the idea, who was struggling with alcoholism following the failure of his own self-published novel. Together the men approached Rostov, who was so enthused with the idea that it dispelled Kurvitz's doubts, and prompted him to write the single-page synopsis that would lay the groundwork for Disco Elysium: "AD&D meets '70s cop-show, in an original 'fantastic realist' setting, with swords, guns and motor-cars. Realized as an isometric CRPG – a modern advancement on the legendary Planescape: Torment and Baldur's Gate. Massive, reactive story. Exploring a vast, poverty-stricken ghetto. Deep, strategic combat."

RELATED: Former BioWare Writer Starts New Studio to Focus On Narrative-Driven Games

Anyone who has played Disco Elysium will notice that a few of these ideas were pruned away by the time the game finished development, but that the soul of the idea still shines through. The poverty-stricken ghetto of the game is not exactly vast in scale, but it is in depth and lore. The swords are also absent, nor is there any combat to speak of, and moments of tension and violence are resolved through skill-checks no different to normal dialogue.

The development process began at once, based out of a squat in Tallinn's old town, and soon ZA/UM, the creative's collective that had begun as a D&D group, was transformed into a games studio. In 2016, No Truce With the Furies was announced, after ZA/UM managed to secure a first round of venture capital financing. Then, in 2017, the game was listed as one of seven titles that would be published by the newly-founded Humble Publishing, though ZA/UM would move away from Humble before release and the game is now self-published. Finally in 2018, No Truce With The Furies was replaced as a working title by Disco Elysium, just one year before its launch and near-overnight success.

At the time of writing, ZA/UM consists of 35 in-house developers, 10 of which are writers, as well as around 20 independent contractors attached to the studio. Not triple-A numbers by any means, but then they've proven that those numbers aren't what's necessary to make a great RPG. It's true that Disco Elysium isn't for everyone, and the sheer volume of text and world-building that the game provides will certainly put some off. But for those prepared to put in the time, Disco Elysium will prove that a unique, well-written and beautiful RPG is within the reach of even the smallest of studios.

Disco Elysium is out now for PC, and will be released for Xbox One and PS4 in 2020.

Post a Comment